Transgenic animals are organisms genetically modified to contain one or more foreign genes, known as transgenes, inserted into their genome. These transgenes can be introduced using various genetic engineering techniques, with the goal of conferring specific traits or characteristics onto the animal. In the context of antibody discovery and therapeutic development, transgenic animals can be engineered to express human antibody genes, enabling them to produce fully human antibodies for research and therapeutic purposes. These animals serve as valuable tools for studying gene function, modeling human diseases, and producing biopharmaceuticals, contributing significantly to biomedical research and drug development efforts.

An increasing number of therapeutic antibodies derived from transgenic animals are fully human, offering significant clinical benefits. Techniques such as gene targeting and the integration of human gene loci via bacterial or yeast artificial chromosomes into rodents, or human chromosome fragments into large animals like cattle, have been instrumental. Although these animals can produce specific human immunoglobulins in serum after immunization, the interaction of human constant regions with the endogenous signaling components in these transgenic animals has been less efficient compared to wild-type immunoglobulins. Advances in genetic engineering, like linking human V-region genes to endogenous C-region genes, have led to improvements in antibody yield and immune response, mimicking those of non-modified animals.1

The Rise of Transgenic Animal Models in Antibody Discovery

Innovations in genetic engineering have enabled the integration of human immunoglobulin genes into the genomes of mice, rats, rabbits, chickens, and even cows, thus equipping them with the ability to produce human antibodies through their natural biological processes. This in vivo antibody generation provides many benefits, such as recovering molecules that bind to the target antigen with high specificity and affinity. Further in vivo sequence diversification, somatic hypermutation, and tests for quality control allow for the non-random selection and enrichment of B cells that yield antibodies possessing therapeutically favorable attributes.2

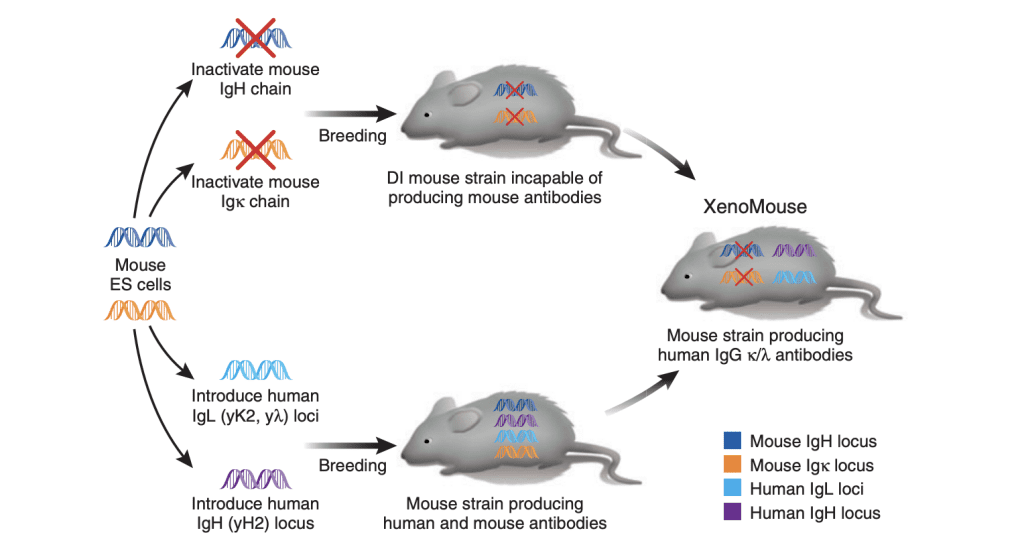

This technological leap has resulted in the creation of platforms like XenoMouse and HuMab-Mouse that have been instrumental in the development of numerous therapeutic antibodies. The technology mimic essential elements of the human antibody repertoire, including usage patterns of V-, D-, and J-segments. The capacity to integrate mouse biology with human antibody sequence data granted researchers access to a diverse source of fully human antibodies, which has since been extended to other species.3

Advantages of Humanized Transgenic Animals

Humanized transgenic animals offer a valuable tool for antibody discovery and development. The use of antibodies with fully human idiotypes can reduce the risk of immune rejection in patients often associated with non-human antibodies. Humanized transgenic animals can also provide a more accurate model of human immune response compared to traditional animal models, allowing for better evaluation of potential antibody therapies before human trials. Moreover, these platforms enable rapid and efficient antibody discovery and development, broadening the scope of treatable diseases with biologics that exhibit high specificity and affinity.

- Brüggemann, M., Osborn, M. J., Ma, B., Hayre, J., Avis, S., Lundstrom, B., & Buelow, R. (2015). Human antibody production in transgenic animals. Archivum immunologiae et therapiae experimentalis, 63(2), 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00005-014-0322-x

- Chen, W. C., & Murawsky, C. M. (2018). Strategies for Generating Diverse Antibody Repertoires Using Transgenic Animals Expressing Human Antibodies. Frontiers in Immunology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00460

- Akkina R. (2014). Humanized Mice for Studying Human Immune Responses and Generating Human Monoclonal Antibodies. Microbiology spectrum, 2(2), 10.1128/microbiolspec.AID-0003-2012. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.AID-0003-2012

Share: